How to legalize building more homes in your NYC neighborhood

You have a surprising amount of power to change New York’s land use rules

Finding an affordable apartment in New York City can feel like an impossible dream, leaving many New Yorkers struggling with skyrocketing rents and a vacancy rate hovering near record lows. But what if you could help change that? What if you had the power to make it legal to build more homes in your neighborhood?

The simplest lesson of economics is that rent – like all prices – is set by supply and demand. When lots of people want to live in an area, rent goes up. When the supply of homes is plentiful, rent goes down.

A lot of people are willing to pay a lot of money to live in New York. Yet, as I’ve covered previously, New York has extensive rules that restrict building more apartments that could house thousands more New Yorkers – and reduce housing costs for everyone. The result is that as of 2023, just 1.4% of New York’s rental housing was vacant, and the median New Yorker who rents their home pays their landlord 31% of their pre-tax income.1 This is bad!

The good news is that New York’s land use rules can be changed – and there’s actually a surprisingly accessible process that anyone can use to get amendments to the city’s housing rules in front of decision-makers. In this post, I’ll explain how ambitious supporters of the Abundance Agenda can use New York’s zoning process to legalize building more homes, and help make our city a more prosperous and affordable place to live.

How to reform NYC’s land use rules (in brief)

In essence, the process to change New York’s land use rules is:

Understand NYC’s current land use rules

Figure out what land use rules you think should apply to your area

Determine who will propose what zoning change

Write and submit your proposed zoning amendment

Wait for decisions from the Community Board, Borough President, City Planning Commission, and City Council

The political reality of land use reform

In truth, changing New York’s land use rules is difficult. It requires significant effort and expense to prepare a valid rezoning application, and then substantial political savvy to gain the approval of the City Planning Commission and the City Council. In some parts of the city residents may be too opposed to densification for upzoning to be feasible.

However, the fact that any New Yorker can propose a zoning change gives residents and community groups a surprising amount of agenda-setting power. If you’re able to compile a valid proposal, the system will require your rezoning to be considered by all levels of city government. You’ll get coverage from local news, and an opportunity to make the case to your neighbors for pursuing housing abundance. In the best case scenario, your rezoning succeeds, more homes get built, and housing costs reduce for everyone. But even if your rezoning proposal fails, you at least make it explicitly clear to the community, developers, and elected officials that there are many New Yorkers who want to make it legal to build more homes. This helps to shift the Overton window, and can nudge politicians toward taking bolder stances on increasing housing supply.

Achieving housing abundance is a marathon, not a sprint. Working with your pro-abundance neighbors in an attempt to directly legalize building more homes could be a big step towards making New York a more affordable and prosperous place for us all.

How to reform NYC’s land use rules (in detail)

Step 1: Understand NYC’s current land use rules

Before you try to change the law, you first need to understand what it says today. New York’s land use rules are contained in the zoning resolution, which is a 3,000+ page text that dictates the permitted forms and uses of buildings in every part of the city.

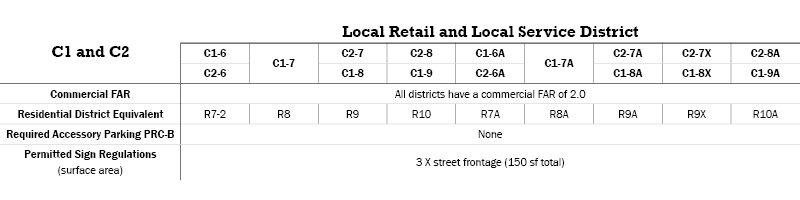

Each property is in a zoning district, which defines what rules apply. For example, my building is in an area that is zoned “C1-9”. This means the land can be used for commercial and residential purposes, typically with shops on the ground floor, and a tower of apartments above. Most retail, medical, and office uses are allowed in a C1 district, but more disruptive uses like motor vehicle repair, car washes, and gas stations are forbidden.2

Each zoning district has a code: a letter and a number (sometimes followed by another letter or number). The first letter of a district’s code – R, C, or M – indicates whether the district is primarily used for residential, commercial, or manufacturing purposes. The number indicates the intensity of building that is permitted, with larger numbers signaling that taller, bulkier buildings are permitted. Additional letters or numbers indicate subcategories of the main zoning district.

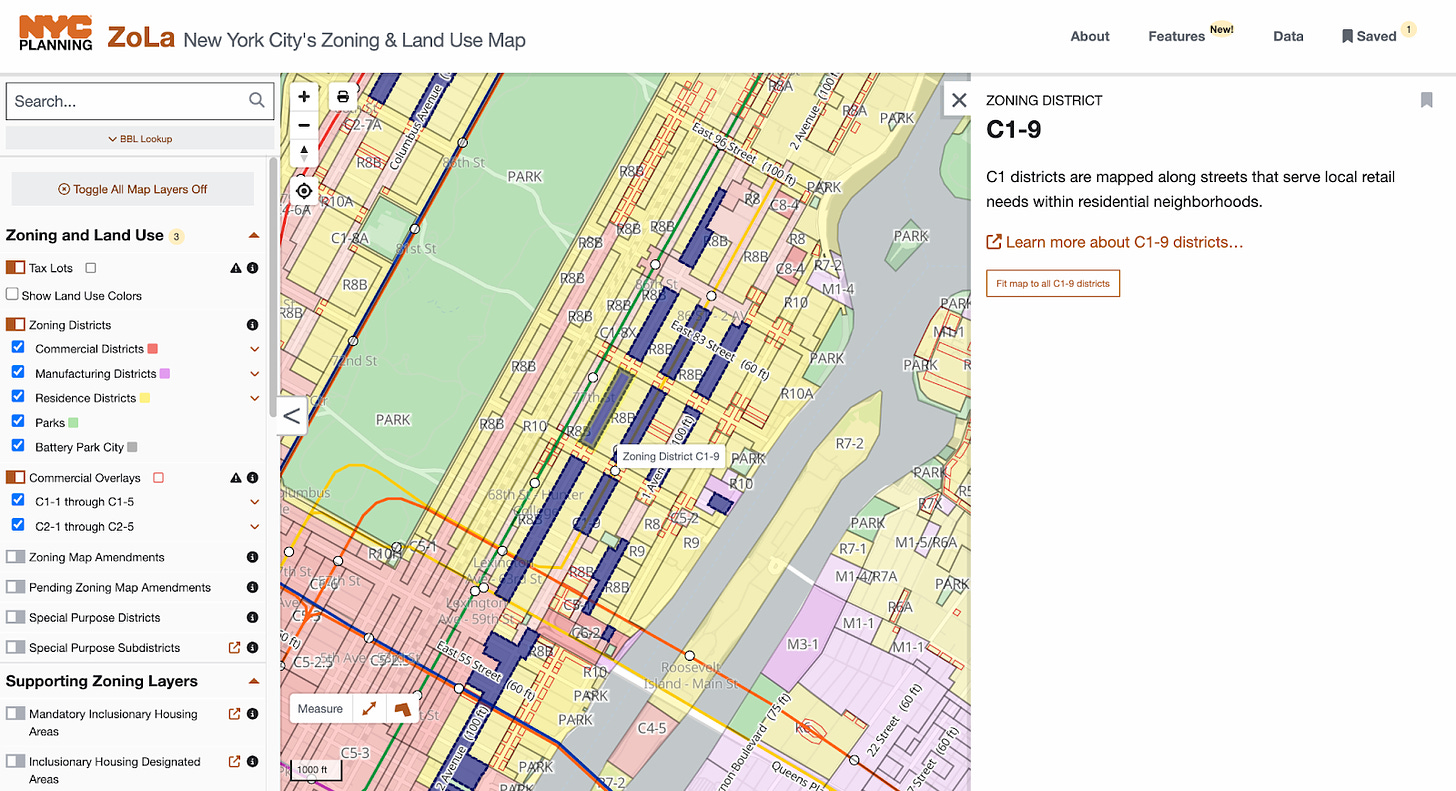

To understand what zoning district covers the areas that you care about, visit ZoLa, New York’s zoning and land use map.

Then, you can browse the DCP’s summaries of the rules that apply in each district. The ultimate source of law is the zoning resolution, but the summaries are much easier to parse. As an example, this is a summary of the restrictions that apply to my C1-9 district:

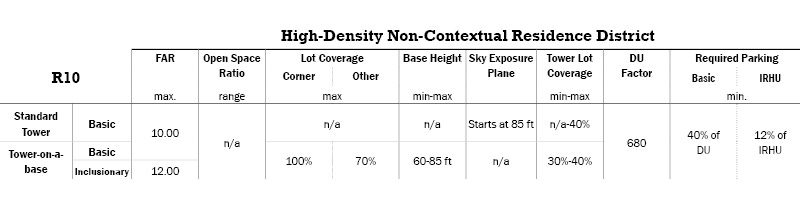

The most important concept is “floor area ratio” (FAR). This determines the maximum amount of floor area in a building that can be allocated for a given use, as a ratio of the zoning lot’s total square footage. For example, a 10,000 square foot lot in a C1-9 / R10 zone can contain at most 2.0 × 10,000 = 20,000 square feet of commercial space, and 10.0 × 10,000 = 100,000 square feet of residential space. This floor area is further constrained by other restrictions, such as how much of the lot can be covered by a building. Floor area “bonuses” can be granted for providing amenities like public plazas or by allocating a proportion of the apartments to low-income renters at below market-rate.3

I’ve found that the best way to understand zoning is to walk around my neighborhood (or fly around on Google Earth), and then cross-reference buildings I see in the real world with ZoLa to identify their zoning district.

Step 2: Figure out what land use rules you think should apply to your area

Then, you need to work out what you’d like to change. Would you like to allow taller buildings with a greater residential floor area ratio? Or maybe make it legal to build apartments on top of shops in an area where this is currently forbidden? In theory, anything is possible. The easiest path is to identify another neighborhood you’d like to emulate, and study what zoning applies in that area.

Step 3: Determine who will propose what zoning change

Under the city charter, anyone can propose a zoning change.4 If you propose your change as an individual person or business, you have to pay thousands of dollars in application fees, but if you get a government entity (including a Community Board) or a non-profit to propose your change, then the application fees are waived.5

You need to decide exactly what zoning changes you want to propose. The two most common are:

Zoning text amendments, which change the rules that apply within the existing zoning boundaries. For example, you could increase the residential floor area ratio in all R10 districts from 10 to 11, which would allow for taller apartment buildings that could house more New Yorkers.6

Zoning map amendments, which change which zoning districts are in force in a particular area. For example, you could take an area that is currently zoned R8A and propose to upzone it to R9A, which would allow for taller, denser buildings. This change would only apply to the properties or blocks you specifically target in your proposal.

If you’re focused on a specific area, a zoning map amendment is likely the most simple path of action. If you want to make changes across the whole city (such as the current City of Yes reforms), you’ll need to make a zoning text amendment.

Step 4: Write and submit your zoning application

Meet with the Department of City Planning to get advice on your proposal, and then complete a land use application form. These applications can be complex, so it might be worth hiring professionals to advise you on how to prepare the documents.

You can browse all past and pending zoning applications online. Here’s an example of rezoning a group of properties in Queens, and rezoning East Midtown in Manhattan. Click through to the “Public Documents” to see all the attachments.

Step 5: Review by the Community Board, Borough President, City Planning Commission, and City Council

Your proposal will then be reviewed by the city’s elected and appointed officials. You’ll need to deploy your most persuasive arguments and all your political capital to convince these decision-makers to support your reform:

Within 60 days of your proposal, the relevant Community Board will meet to hear public comments on your proposal and vote to recommend the approval or disapproval of your proposal.7 While this recommendation is simply advisory, the City Planning Commission often gives significant weight to the perspectives of impacted residents. (You can learn more about Community Boards in my post from last month.)

Within 30 days of the Community Board’s vote, the Borough President will submit a recommendation to the City Planning Commission that they either approve or deny your zoning amendment request.8

Within 60 days of the Borough President’s recommendation, the City Planning Commission will review and vote to approve, alter, or reject your proposal.9 The 13 commissioners are appointed by the mayor, the borough presidents, and the public advocate. If the CPC rejects an application, the proposal fails.

Finally, within 50 days of the CPC’s decision, the City Council will vote on your proposal.10 If the Council rejects an application, the proposal fails. Typically the City Council’s vote will follow the lead of the Council member who represents the impacted. There are cases where a majority of the Council will go against the wishes of the local Council member, but these are rare. This means that gaining the support of the local City Council member is essential for any rezoning project to succeed.

Step 6: Build, build, build!

If you’ve made it this far, then you’ve won! Once you’ve secured all your approvals, your zoning change becomes the law of the land. Time to pick up your hammer, and get to work on building more homes – or perhaps find a friendly builder to do the construction for you.

A call to action

If reforming New York’s land use rules was easy, we would have done it already. The reality is that almost all rezonings are proposed by professionals: either property owners/developers who want to change the zoning of a specific property, or officials at the Department of City Planning who are executing the vision of the mayor and commissioner. Although New York’s law allows individuals and community groups to initiate zoning reforms, these actions are rare.

Even then, I think it’s worth exploring grassroots efforts to change land use rules. Housing costs are such a critical issue for New Yorkers. There’s a growing constellation of grassroots organizations like Open New York, Abundance New York, and Maximum New York that are giving New Yorkers the skills, support, and direction to best engage with our system of government. With the right effort applied in the right places, reducing rents by legalizing the construction of more homes might actually be within our grasp.

Let’s remake New York into a city where housing scarcity is history.

2023 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey Selected Initial Findings, page 28, NYC Department of Housing Preservation. 2024 Income and Affordability Study, page 18, NYC Rent Guidelines Board.

NYC Zoning Resolution, Section 32-10, NYC Department of City Planning.

Description of Public Plazas and Inclusionary Housing in the description of R10 districts, NYC Department of City Planning.

New York City Charter § 201, American Legal Publishing.

Rules of the City of New York § 3-06, American Legal Publishing.

If you’re trying to improve R10 zones, you might also need to adjust sky exposure plane restrictions, which also impact how tall buildings can be.

New York City Charter § 197-c(e), American Legal Publishing.

New York City Charter § 197-c(g), American Legal Publishing.

New York City Charter § 197-c(h), American Legal Publishing.

New York City Charter § 197-c(c), American Legal Publishing.

I didn’t know community boards could propose rezonings! Very informative.

Beautifully explained, Sebastian.