How Third Avenue was made safer and faster for pedestrians, bus riders, and cyclists

Advocates built a movement that successfully convinced New York City's government to install a bus lane, bike lane, and intersection safety improvements on Third Avenue

New York’s streets form the bulk of our city’s public space. The way we configure our roadways directly impacts how New Yorkers get around, shop, and play.

2023 saw a major transformation of the Upper East Side portion of Manhattan’s Third Avenue. Over the summer, the NYC Department of Transportation (DOT) completely revamped the section between 59th and 96th Streets to be safer for pedestrians and bikers, and faster for bus riders.

This reimagining of Third Avenue was the direct result of New Yorkers mobilizing to demand safer, more liveable streets from the city government. Two Manhattanites, Paul Krikler and Barak Friedman, led a community campaign that convinced the Department of Transportation to act. In late December I met with Paul to learn about the history of the project and see what lessons we can draw for advocates elsewhere in the city.

My takeaways:

New Yorkers loudly calling for safety and transit improvements has a big impact. Mobility advocates making a lot of pro-safety and pro-transit noise is essential for the DOT to demonstrate it has the social license that’s necessary to overcome tepid mayoral support and fear of backlash from car owners.

Effective street reform campaigns require patience and partnership. Third Avenue’s transformation took 2.5 years from conception to completion – which was actually faster than similar projects in recent decades.

The Story of Third Avenue

One day in spring 2021, Paul Krikler was biking up Manhattan’s East Side. He was on Madison Avenue, and got frustrated that his nearest safe way to ride uptown was four whole blocks away, on First Avenue’s bike lane. That’s when the idea of the New Third Avenue Boulevard was born.

Paul saw that Third Avenue was ripe for transformation. It’s unusually wide — 70 feet from curb to curb, with a further 15 feet of sidewalk on each side. On the Upper East Side, Third Avenue cuts through the most densely populated square mile anywhere in the United States or Europe. The avenue is lined on each side with tall apartment buildings on top of ground floor retail. 84% of Upper East Side residents commute to work or school by public transit, by bike, or on foot.1 These factors combine to make the Upper East Side portion of Third Avenue an excellent space for human-focused safety improvements and speeding up the area’s buses.

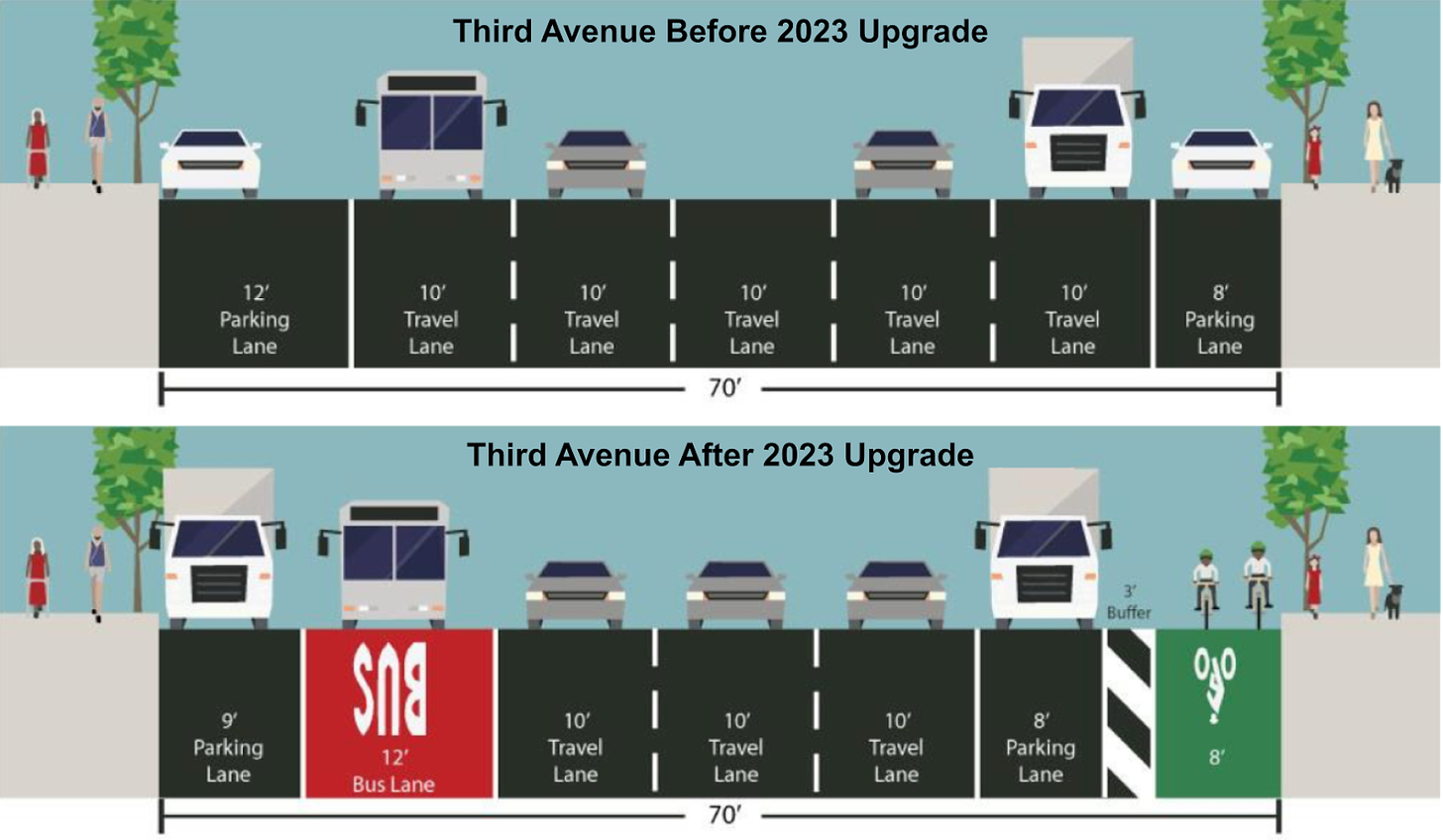

Before 2023, Third Avenue was entirely dedicated to cars. It had five lanes for vehicles and a lane of parking on each side. The avenue was dangerous: it had been the site of 37 severe injuries and seven vehicle-related deaths between 2016 and 2022.2

Against this backdrop, Paul embarked on a campaign to revamp Third Avenue. He teamed up with Barak Friedman, another local resident, to lobby the NYC Department of Transportation to add a bus lane, a bike lane, and intersection reconfigurations to make Third Avenue safer for people walking and biking, and faster for bus riders to travel along. These roadway upgrades didn’t require any law changes or budget allocations; repainting road markings and the relatively small cost of bollards and bike racks are within the DOT’s standard remit.

To gauge public interest in their proposal, Paul and Barak fielded a petition — mostly in-person walking along Third Avenue. That quickly reached 400 signatures, which was enough for Transportation Alternatives, an advocacy group, to make improving Third Avenue an official part of their campaign efforts.

Over the following months, armed with some snazzy graphics, the campaign steadily built momentum. An increasing number of Upper East Side residents became convinced that refocusing Third Avenue’s space to focus on people, rather than cars, would be a big benefit for the neighborhood.

Paul and Barak tried everything to bring attention to the campaign. They created a website and a social media presence. They knocked on doors of businesses along the avenue. They chatted with local residents at Open Streets events and held a “People’s Choice Awards” for street safety advocates across the city. They wrote an op-ed in Streetsblog. The got on local TV. They secured support from local city council members, and got buy-in from Mark Levine, who was then a candidate for Manhattan’s Borough President position. They met with officials at the DOT.

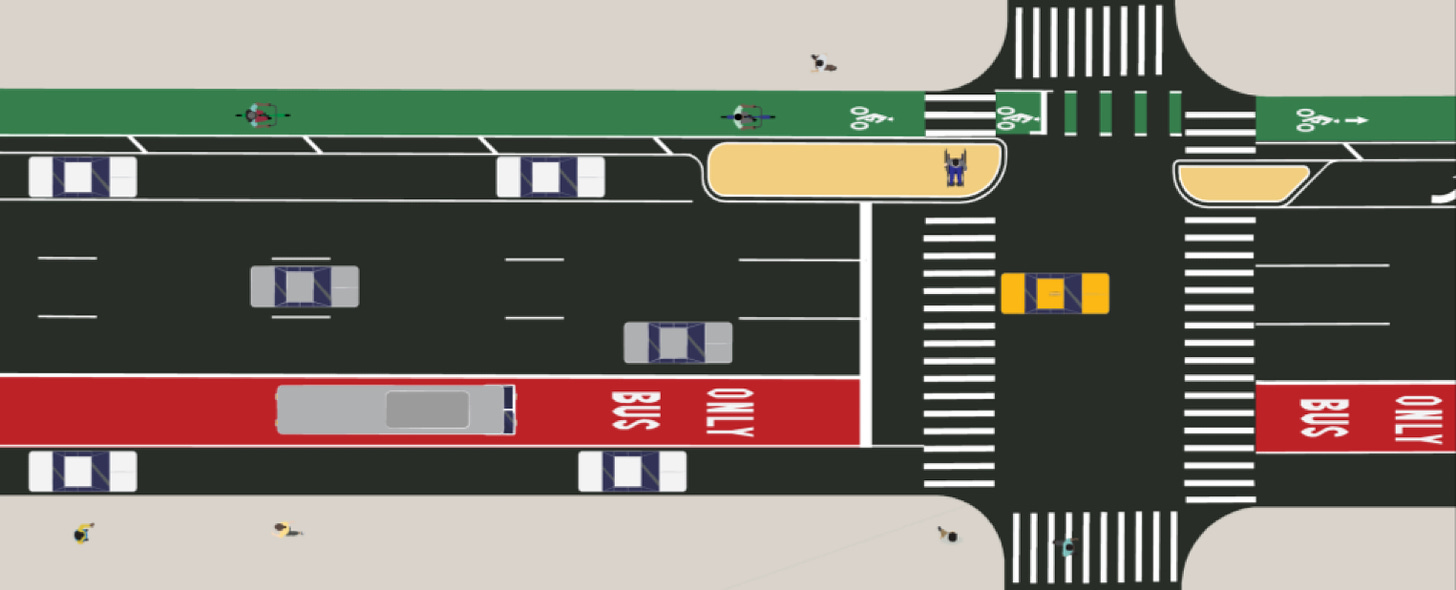

Ultimately, in October 2022, the DOT presented a proposal to revamp Third Avenue to Manhattan Community Board 8, which covers the Upper East Side. This plan included an extra-wide bike lane protected by a lane of parked cars, a dedicated lane for buses, and “daylighting” around intersections to improve pedestrian safety.

At the Community Board meetings dozens of people who live or work in the neighborhood voiced their support for the changes (including me!).3 Even several people who just commute through the Upper East Side hopped on the Zoom call to share their enthusiasm for how the changes would make their trips faster and safer. While this proposal didn’t go quite as far as many advocates had hoped, the changes were undoubtedly a significant improvement over what existed at the time.

The primary opposition came from people who feared that New Third Avenue Boulevard might reduce the availability of on-street parking and slow down cars. Only 39% of Upper East Side households own a car, and just 16% of UES residents drive to work, but car owners care a lot about changes to the roadway and aren’t hesitant to make their voices heard. These car owners’ concerns were sometimes framed as worries about “slowing down emergency vehicles” or “hurting local businesses that depend on customers driving to do their shopping”. These fears are obviously misplaced when you remember that emergency vehicles are allowed to use bus lanes, which likely makes them travel faster, and that car-based shopping is already incredibly rare on the Upper East Side.

After many hours of public testimony and debate among the 50 appointed members of the community board, the community board finally passed a resolution endorsing the DOT’s proposal on 19 October 2022.

Getting sign-off from the community board was a big deal for the project. While resolutions of NYC community boards aren’t legally binding, city agencies are highly deferential to them. At a minimum, agencies rarely pursue any project that is actively opposed by the majority of a community board.

Implementation

After the approval from the community board, it was just a question of waiting for the weather to warm up. (NYC doesn’t do any changes to road markings over winter because the paint can’t dry properly in the cold.)

Finally, over summer of 2023, the DOT implemented their plan. They scrubbed away the old road markings, laid down new lines, filled the bike lane with “Kermit” green paint and the bus lane with a deep red. Finally, the crews installed bollards and bike racks.

Lessons from Third Avenue

I think the upgraded Third Avenue is awesome. The pedestrian islands on the west side of the avenue make it easier and faster to walk across the avenue. The parking-protected bike lane feels remarkably safe, and the traffic calming elements around intersections make a big difference at slowing down turning vehicles and preventing bike riders from getting hooked from the side.

Third Avenue isn’t perfect, though. The bus lane is often illegally blocked by delivery trucks. The posts that surround pedestrian islands and delineate the bike lane are made of plastic, which means they provide negligible protection against carelessly driven or out-of-control vehicles. Almost half of Third Avenue’s width remains dedicated to the movement and storage of cars and trucks.

That said, Third Avenue has been greatly improved, and I feel lucky to live near such a thriving and vibrant corridor. Here’s a video of a celebration bike ride that Paul, Barak, and I participated in:

From my chat with Paul about his experience with the campaign, these lessons stood out to me:

Working with a partner helps a lot. Paul emphasized that his collaboration with Barak gave him someone to bounce ideas off, share the workload, and keep morale high.

Public advocacy makes a big difference in convincing the DOT to take action. It appears the DOT struggles to proactively set forth a vision for pro-bus, pro-bike, and pro-pedestrian revamps of the streetscape. Ideally the DOT would autonomously go forth and build bus lanes, bike lanes, and safer intersections throughout the city — as they are legally required to do. For a multitude of reasons that isn’t happening. That means that campaigns to demonstrate public support remain essential parts of making change happen.

Compelling visuals of the transformation you’re trying to pursue are essential. Paul said that having a graphic showing their desired end-state of Third Avenue was vital to their campaigns on social media and in-person interactions on the street. Most New Yorkers are leery of a person approaching you with a clipboard, but a clear graphic and simple title, like “The New Third Avenue Boulevard” helps to draw people in and start imagining themselves on that transformed street.

Above all, I see in this campaign the importance of knowing clearly what your goal is. Paul and Barak specifically wanted the DOT to take action to revamp Third Avenue’s streetscape. They built a movement around that objective, got buy-in from influential stakeholders, and made change happen in the real world.

And New York is all the better for it.

If you’d like to help improve New York’s streetscape, take a look at the work of groups like Transportation Alternatives and the Riders Alliance. There are always projects that need more helping hands.

Upper East Side Residents' Mode of Transportation for Travel to Work, IPUMS USA (requires free account to access data)

NYC DOT Celebrates Completion of Major Safety Project on Manhattan's Third Avenue, NYC Department of Transportation

Wonderful read. I hope we see more activist movements in the city like this - the USA is notoriously behind the curve with bicycle and pedestrian focused design. Successful initiatives like this set a good example to follow.

Wow, this is awesome. It really comes down to three P’s: a partner, petitions, and pictures. That’s a potent playbook