New York's unfair property tax system: a tale of two buildings

How the city government’s largest revenue source creates winners and losers

Imagine owning an apartment in a $6 million co-op building in Queens and paying nearly six times more in property tax than someone with a $6 million single-family home in Manhattan. It's not fiction; it's the stark reality of New York's property tax system — a system that quietly yet dramatically impacts every resident. From the schools that educate the city's youth to the parks, public transportation, and emergency services we all rely on, property taxes fund a third of the city's essential services. Yet, how many of us understand this vital revenue source?

I’ve spent the past month digging into New York’s property tax system. Here’s the breakdown:

Property tax is a lot of money: The city collects $31.6 billion in property taxes each year, which is equivalent to $3,589 per New York resident.1 It’s the city’s largest revenue source.

NYC’s system is pretty unfair: Properties with similar values often get wildly different tax bills due to special treatment for certain types of homes.

Property tax shapes our city: Tax policy influences what gets built. Our current system suppresses construction of apartment buildings.

Tax policy isn't glamorous, but it affects every New Yorker. This post is the first in a series aimed at dissecting New York's convoluted property tax structure, exposing its inequalities, and exploring how we can build a fairer system for all New Yorkers. Over the coming months, I'll cover:

An introduction to NYC’s property tax system (this post)

How land value taxes offer a path to housing abundance and prosperity

Property Tax 101: What You Need to Know

Property taxes in New York City are a crucial part of the city’s finances, levied on virtually all land and buildings. This includes not just residences—whether single-family houses or apartment complexes—but also commercial properties like shops, offices, and factories, as well as utilities such as power plants.

However, there are exceptions. Properties owned by city, state, or federal governments, public authorities like the Port Authority, and foreign embassies are exempt from property tax. Additionally, some nonprofits offering educational, religious, or medical services are exempt.

So how does the city go about collecting these taxes?

Each year, the City government estimates the value of every property.

The mayor and the City Council determine the total revenue they aim to collect from property taxes. State law caps this amount at 2.5% of the total market value of all properties in the city. In practice, the city tends to collect about 2.4% of the market value, which in 2022 amounted to $31.6 billion.2

The City’s Department of Finance uses state-mandated formulas to calculate the tax for each property owner. These calculations are influenced not just by the property’s estimated value, but also by its type and tax history.

It's worth noting that the impact of property taxes isn’t restricted to property owners. Landlords ultimately pass all of their operating costs through to their tenants. Likewise, commercial properties pass along their tax burdens to consumers through the cost of goods and services. In essence, property taxes impact everyone, not just property owners.

NYC’s property tax burden is spread unevenly

In my ideal property tax system, properties of similar value would pay a similar amount of tax. That is categorically not the way New York’s property tax system works, unfortunately.

Throughout the city there are widespread disparities in the effective tax rate that property owners are charged.3 These differences exist in terms of the property type, location, value, and the number of units it contains.

To illustrate these disparities, consider two properties that are both worth around $6 million:4

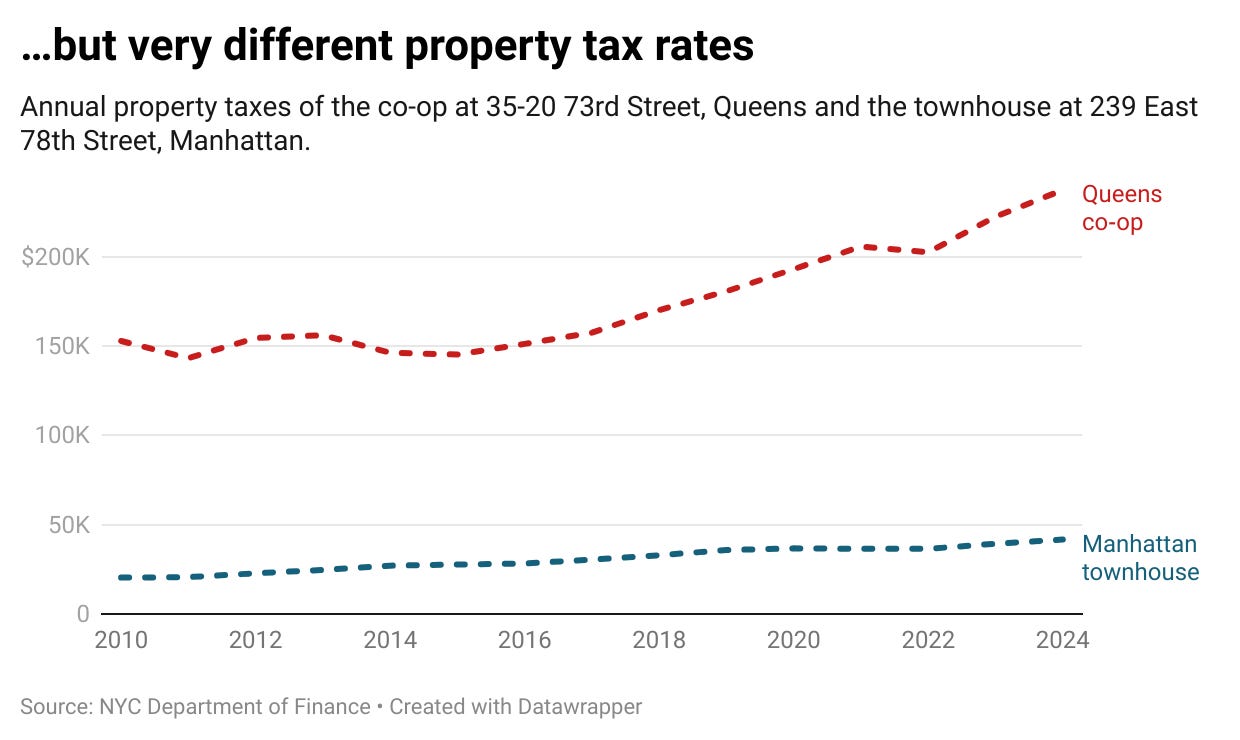

A 6-floor cooperative building containing 96 apartments in Jackson Heights, Queens, at 35-20 73rd Street. The city estimates it’s worth $6.6 million, and its property tax bill is $238,907.5

A 7-floor, 4,000 square-foot, five-bedroom single-family home on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, at 239 East 78th Street. It sold for $6.1 million in 2016, and it’s currently on the market with an asking price of $7.5 million. The city estimates that it’s worth $5.5 million, and its property tax bill is $41,697.6

The Manhattan townhouse is taxed at 0.76% of its market value, while the Queens co‑op building is taxed at 3.62%. That’s a huge difference!

To be clear, it appears that both of these property owners are perfectly following the law. No one is breaking any rules – it’s just that the application of our tax policy results in these very different tax bills for two ostensibly similarly valued properties.

Differences in assessed value growth restrictions are the main cause of these very different effective tax rates. This policy limits how much a property’s tax bill increases when a property’s market value increases.

Tax bills for properties containing 1, 2, or 3 residential units are only allowed to increase by at most 6% year-on-year and 20% per rolling 5 year period.

Tax bills for properties containing 4 to 10 residential units are only allowed to increase by at most 8% year-on-year and 30% per rolling 5 year period.

There are no limits on the increases in tax bills for properties with 11 or more units, but any changes in value are phased in over a 5 year transition period.

These restrictions were originally implemented to protect homeowners from financial distress due to sudden spikes in their property taxes. While the restrictions certainly accomplish this goal, the differently structured policies based on property size create disparities in effective tax rates across properties of similar value – only based on the number of units in the property.

Going back to our Manhattan/Queens example, the reason the Manhattan home pays so much less tax than the similarly-valued Queens co-op apartment building is that the Manhattan home’s tax increases have been limited as its value has grown, but the Queens building’s tax increases have risen in proportion to its increase in value. Since 2013, the Manhattan home’s market value has increased by 102% while its tax bills have increased by 54%. In contrast, the Queens co-op’s market value has increased by 85% while its tax bills have increased by 62%. The Manhattan home’s tax bill would have increased more significantly, but it was capped by the 6% year-on-year or 20% five-year legal limits. The tax growth on the Queens co-op is unrestrained.

In sum, our unfair tax policies result in wide differences in tax bills based solely on how many units are in the building.

The impact

Our property tax system disproportionately burdens apartment residents with higher tax rates than single-family homeowners. Not only is this unfair, it’s also regressive: New York charges its least wealthy homeowners higher tax rates than its most wealthy. This contradicts the conventional wisdom of taxing the wealthy at higher rates to fund public services.

This policy stifles housing construction. Higher ongoing tax costs make multi-unit properties less appealing to both buyers and developers. If there are two identical properties with different tax rates, any savvy buyer will demand a discount to purchase the higher-taxed home. In aggregate, this depresses the value of higher-taxed apartments, which reduces the appeal for developers to construct large apartment buildings.

This effect is most obvious at the cutoffs of the growth policy for property taxes. If you construct a building with 10 apartments your tax bill will be limited to increases of at most 30% every 5 years. Adding an 11th apartment to those blueprints will instantly subject the entire property to unconstrained tax increases. This tax penalty is often sufficient to dissuade a developer from adding another unit that could have welcomed another family to New York and slightly reduced housing costs for everyone.

Our distorted property tax system penalizes owners of units in larger buildings, suppresses housing construction, and pushes up the cost of living for the average New Yorker.

What’s next

We’ve only just scratched the surface of New York’s complex property tax system. It’s a big topic, so I’ll pause here, for now.

To dig more into proposals to reform New York’s property tax system, and why these efforts seem to have stalled, see my follow-up post:

Annual Report of the New York City Real Property Tax for fiscal year 2022, page 7, The City of New York Department of Finance (archive). That citywide levy is divided by NYC’s population data from the NYC Department of City Planning.

Ibid.

To be clear: I have no connection with either of these properties; I just found them while browsing through NYC’s tax databases. All property tax records are public data!

Property Tax Summary for 35-20 73rd Street, Queens. NYC Department of Finance. (archive)

Property Tax Summary for 239 East 78th Street, Manhattan. NYC Department of Finance. (archive)

Thank you for writing this really informative article on New York City's property tax system. I learned a lot about the disparities in tax rates which seems like is calling for reform. It is really concerning that this hinders multi-unit housing construction. Do you know if there are proposals or policy changes that are being considered to rectify these inefficiencies in the city's property tax system?

I don’t understand how you wrote a whole article about property taxes but didn’t actually explain how condo/co-op property taxes are based on comparable rents and not market values, which in of itself is regressive because super expensive condos do not really have comparable rents, which means they end up paying taxes that end up being a much smaller fraction of the property value than a cheaper condo or co-op