Why housing is so expensive in New York

A look into zoning, historic preservation, and how we could reduce housing costs

A couple of weeks ago some good friends of mine on the Upper West Side got news that their rent is going up by 15%. They’re thinking about leaving Manhattan to move somewhere cheaper. This month another friend is moving from Chelsea to Jersey City after she found a much better deal there. Other friends have told me about brokers asking for bribes, fierce competition for leases, and general low availability throughout the city.

New York’s housing market is clearly hot and isn’t working well for my friends, so I wanted to dig in: why is housing so expensive in New York City?

Sidebar: Housing is a huge topic, and I’m not going to be able to address it all in one post. My goal for today is to equip you with some facts about New York’s housing situation and lay the foundation for writing more posts on this topic.

New York’s housing market

New York is a city of renters: 66.7% of New York households rent, compared to a nationwide average of 34.6%. These families pay a lot: 54.1% of NYC’s renting households are “rent burdened”, meaning they pay more than 30% of their income on rent.1 The average rent for a one bedroom apartment in Manhattan is $4,289 per month, as of April 2023.2

Fundamentally, housing prices are a question of supply and demand: how many people are willing to pay what prices to live somewhere, and how many housing units exist in that area?

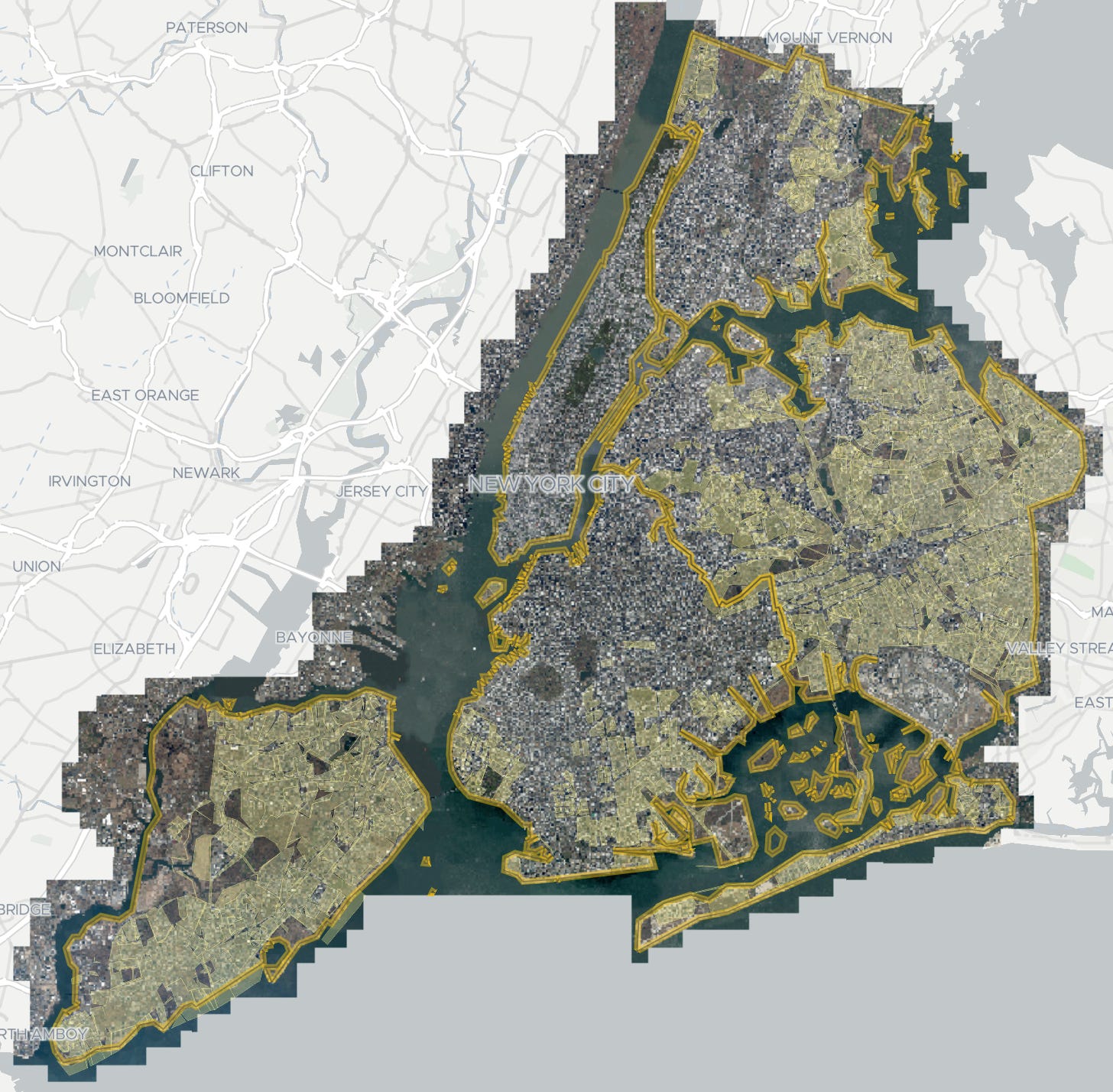

On the supply side, over the past decade New York has constructed 27,000 new homes per year. In 2021 the city had 8% more housing units than in 2010.3 Most of this construction has been happening in Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. Areas like Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City have become much more dense over this time:

New York’s newly constructed housing units all get filled by the city’s growing population, which also grew by 8% between 2010 and 2020. People are eager to become New Yorkers, even at these high prices!

Despite this increase in housing supply, rents keep increasing. According to Census Bureau data, New York City’s median rent in real terms (which adjusts for inflation) increased 14.2% between 2010 and 2021.4 This increase in rents shows that demand for housing is growing faster than supply. There are far more people who are willing and able to pay a lot of money to live in New York than there are places for them to live. The direct negative consequences of this are:

New Yorkers have to pay huge proportions of their income for housing. This leaves us with less money to spend on health, food, education, and our passions.

Millions of people who would like to live in New York City are kept out – unable to move here because there aren’t enough homes for them to live in.

Some existing New Yorkers get pushed out of the city when housing costs rise faster than their incomes.

As readers of Sidewalk Chorus know, I think that New York is a great place to live. At the macro level, I want as many people as possible to have access to the joys of life in New York City and have the opportunity to thrive here. Compared to almost all other places in the US, New York is much safer, produces lower per-capita carbon emissions, and has longer life expectancy. On a personal level, I want my friends to remain close. It makes me sad that rising housing prices are threatening to push them away.

The obvious way to address this problem of supply and demand and reduce housing prices is to build more homes.

New York’s rules against building

In a market for a normal product or service, when the market price goes up it provides motivation for producers to increase their supply. Unfortunately New York City’s laws contain several critical restrictions on building more housing. In much of the city these restrictions make it either illegal or uneconomical to build taller and denser buildings that could be home to more New Yorkers and reduce costs for everyone.

The Zoning Resolution

New York City’s zoning resolution restricts the construction of new homes. Under this law, each parcel of land is subject to rules about what buildings can legally be constructed on the land. Zoning also controls whether each piece of land may be used for residential, commercial, or manufacturing purposes. The zoning resolution includes rules about:

The number of housing units may be built on the lot (single-family, two-family, or multi-family)

The maximum proportion of the lot that may be built on (the open space ratio)

The maximum amount of residential floor space than may be constructed, relative to the lot’s size (the floor area ratio)

The minimum lot size

The minimum depth of yards at the property’s front, sides, and rear

The minimum and maximum height of the building

The minimum number of off-street car parking spaces the property must have

For example, areas that are zoned as R1 single-family detached residences are subject to the following requirements:

These rules mean that anyone who is building a home in an R1 area must have a front yard of at least 20 ft depth. Even if the landowner doesn’t want a yard and would rather have a larger dining room, New York’s zoning rules forbid it. Yards are mandatory in R1 zones.

These zoning rules also specify requirements for hundreds of other aspects of buildings, such as the dimensions of awnings (at most 2 feet, 6 inches), the maximum width of building columns (“not more than 20 percent of the aggregate width of street walls of a building”), and the number of washing machines that an apartment building must have (one machine per 20 dwelling units).

Despite New York being commonly known as a place with many tall buildings, the city’s zoning resolution forbids the construction of dense housing in many areas. Throughout essentially all of Staten Island, most of Queens, and much of Brooklyn the maximum floor area ratio is 1.0, which basically only allows single-family homes to be built.

An analysis by Columbia University’s Center for Urban Real Estate has projected that 350,000 more housing units would have been constructed in New York if the city didn’t have floor area ratio limits. These units could have housed 842,000 people and reduced housing costs for all New Yorkers. When you add the restrictions imposed by all the facets of the zoning resolution – minimum yard sizes, parking requirements, and similar – it’s easy to see that these rules are holding back the development of hundreds of thousands of homes.

Landowners are able to apply to the city for exemptions and changes to the rules that apply to their property. This process, however, is long, slow, and often unsuccessful. The fact that so much of the city remains low density shows how sticky these rules are, even in the face of potentially huge financial gains for property owners if they were able to build denser housing on their land.

New York’s zoning rules were put in place in 1961 with laudable goals of “protect[ing] public health, safety and general welfare”. Lawmakers were keen to protect residents from “offensive noise”, “heavy traffic”, and “congestion”. They sought to “open up residential areas to light and air” and ultimately “provide a more desirable environment for urban living in a congested metropolitan area”.5 The city’s population had been stagnant for two decades and the suburbs were on the rise.6 Although the rules have been amended periodically since 1961, their core tenets remain unchanged over the 60+ years since.

These zoning rules might have made sense at one point. Today, however, with advances in construction technologies and the clear demand for high-density urban living, I think New York’s zoning rules now do more harm than good. Our city’s zoning has produced many pretty suburban areas and quaint low-density neighborhoods, but at great cost to the wallets and “general welfare” of every New Yorker whose housing costs are inflated as a result – let alone every person who would love to live in New York but who is priced out.

Historic Preservation

The next thing that holds back housing is historic preservation requirements. These rules freeze buildings in time. Areas subject to these rules are especially common Manhattan and northern Brooklyn. Specifically, New York’s historic preservation rules forbid any changes to affected buildings that would:

“Change, destroy or affect any exterior architectural feature” of a protected building

“Not be in harmony with the external appearance of other, neighboring [buildings]”

Inappropriately affect the building’s “aesthetic, historical and architectural values and significance, architectural style, design, arrangement, texture, material and color”

It is very difficult for the owner of a protected building to alter or expand the building. Many of these buildings are low-density housing, such as brownstones or low rise apartment buildings.

These historic districts include some of New York’s most expensive areas that are very well served by public transportation. These areas would be excellent candidates for building more housing.

These historic preservation rules exist in addition to zoning rules, and essentially impose a hidden tax on all New Yorkers. Without these historic preservation rules property owners would be more free to redevelop these protected buildings into more dense housing for more New Yorkers, which would reduce housing costs. It is possible for a landowner to apply to the city to increase the maximum allowed floor area ratio of their lot, but this is an expensive and time consuming process that is often unsuccessful.

These historic preservation rules lead to ridiculous outcomes. There is an empty lot in Lower Manhattan the size of a football field that various developers have been trying to build housing on since 1979. However, because this lot is in the South Street Seaport Historic District, any construction requires approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Today, 44 years later, after decades of proposals, rejections from the city government, and lawsuits, the site remains empty and barren, providing no benefit – either historical or housing – to anyone.

There probably are a handful of buildings in New York that are genuinely worth preserving: the Empire State Building, Washington Square Arch, Grand Central Terminal, City Hall, and the Custom House at Bowling Green come to mind for me. If their owners were planning to demolish them, I would support using public money to purchase them and open them to the public. But these are mostly publicly owned buildings already.

Is it really worth applying the force of law and raising housing prices to protect these frumpy, privately-owned buildings?

Change is possible

These laws around land use and historic preservation are not set in stone; they are a choice. Our current zoning and historic preservation rules are city-level laws that were passed in the 1960s. A simple majority of the city’s 51 council members and a signature from the mayor is all that’s required to make changes to them.

I think that liberalizing New York’s laws about housing construction is essential. Someone who owns a piece of land should be freely allowed to construct any residential structure they want, so long as the building is safe. No land owner should be forced to build anything, but if they want to build something, we should let them. Want to build a two-storey single family home in Manhattan? Great! Want to build a 6 storey apartment building? Go for it! Want to combine some lots together and scrape the sky with 60 floors of homes in Staten Island? Let’s build!

This liberalization would likely generate huge windfall profits for existing land owners, whose properties would now increase in value because they would now be allowed to house many more people vertically in the same plot of earth. Of course, existing land owners wouldn’t have to build this increased density. If they wanted to keep their current structure, they could. I think it’s even plausible that landowners would be able to use a reverse mortgage borrow against the (significantly increased) value of their land – if they wanted to access that increased value without building today.

But the key is that some landowners would choose to build more denser housing on their properties. This increase in supply is ultimately what will save New York from its own success and reduce the cost to buy or rent a place to live in New York.

Some people will dislike the consequences of what I’m advocating for. If New York does liberalize housing rules, it would almost certainly result in the construction of more apartment buildings. There’ll be noise and dust from construction. The “character” of neighborhoods may change. And there’ll be more pressure on schools, transport systems, and infrastructure. But these are solvable problems. Population growth will be gradual. We’ll have time to build of more classrooms, subway lines, and grocery stores. We have the technology.

But there’ll also be more people who get to thrive in New York and contribute to our great city, with dignity, safety, and a lower average environmental impact than almost anywhere else in the US they could live. New Yorkers will be able to spend less on rent and more on their health, their education, their passions, and their futures.

The political reality is that full liberalization of land use is unlikely to happen any time soon. But even modestly relaxing zoning rules, such as allowing 3 to 5 storey apartments everywhere, could allow for a lot more housing to be built.

And maybe that would be enough to stop my friends from getting priced out of living in New York.

Sebastian

Zoning Resolution of the City of New York, Chapter 1, “General Purposes of Residence Districts”